Liturgy News

Vol 47 No 2 June 2017

Contents

| Title | Author | Topic | Page |

|---|---|---|---|

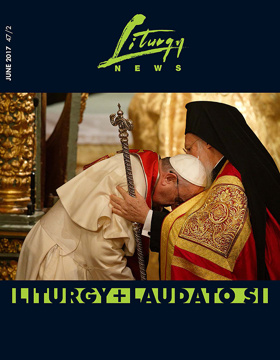

| Our Cover - World Day of Prayer for Creation | - | Creation and Sacraments | 1, 16 |

| Editor: Sad Funerals | Elich, Tom | Funerals | 2 |

| The Anointing of the Sick | Chiera, Tony | Pastoral Care of the Sick | 3-4 |

| Liturgical Ministry of the Deacon | Shanahan, Tim | Ministries – Liturgical | 5-7 |

| Two New Churches - Mary, Mother of Mercy and Stella Maris, QLD | - | Architecture and Environment | 8-10 |

| Deacons in Australia | - | Documents on Liturgy | 11 |

| National Biennial Liturgy Meeting | - | Catechesis - liturgical | 11 |

| Washing of Feet | - | Easter and Lent | 11 |

| Liturgy Bishops | - | People | 12 |

| Handing on the Baton at Liturgy Brisbane | - | People | 12 |

| Blessed Oscar Romero | - | Saints | 12 |

| Fatima | - | Architecture and Environment | 13 |

| Feast of Corpus Christi | - | Calendar | 13 |

| Pope Tawadros and Pope Francis | - | Liturgy - Other Churches/Religions | 13 |

| Good Eucharistic Practice 2: Communion from the Cup | - | Eucharist / Mass | 14 |

| Books: Walk with Me - Christian Initiation for Secondary Students. Catholic Diocese of Sale. | Schwantes, Clare | Christian Initiation | 15-16 |

Editorial

SAD FUNERALS

Elich, Tom

A prominent and greatly respected legal man was buried recently after a Catholic funeral in a venerable parish church. It was a sad funeral. The five eulogies lasted for over an hour. The funeral liturgy which followed – including a two-minute homily – was described by a participant as ‘emaciated’. I think it is sad that Catholic communities no longer seem to know what they are doing at a funeral. They cannot think what else to do besides remembering and paying tribute to the deceased.

The pattern of extended eulogies has become alarmingly common. Often, now that churches have projection screens and display monitors, the words of remembrance will be accompanied by images of the person’s life or multiple images are combined with the soundtrack of the person’s favourite song as a stand-alone item. The expectation that this is an integral part of the funeral liturgy is created by funeral directors and funeral chapels. It is magnified by celebrity funerals held in a stadium or concert venue where the celebration of the dead person’s life is put together in images, video clips, music and testimonial tributes… and nothing more.

I was reflecting on how futile this is recently as I contemplated my own family. I knew my father pretty well – we’d shared six decades of our life. But when I asked about his childhood or what my grandparents were like, I would get the same few stories over and over. Now he is dead and I can ask no more questions. We have some photos. My grandfather in a school band, my grandparents on their wedding day, and so on. Beyond that, yes, I actually have small photos of all eight of my great-grandparents. But of them I know practically nothing. I have names against branches of the family tree going back further still, but how quickly the events and achievements of a human life fade away. I cannot help smiling to myself when I hear the words spoken at a funeral, ‘we will never forget…’

A Catholic funeral liturgy is not, of course, a generic one-size-fits-all affair. It is a particular person, a loved member of a family with a circle of friends, someone with his or her own qualities, talents and foibles for whom we celebrate the liturgy. That is why the liturgy allows for a member or friend of the family [to] speak in remembrance of the deceased. That is why the funeral leaflet might incorporate a photo of the deceased and a short biographical note. That is why the prayers of intercession would include petitions for the various groups to which the person belonged or relating to the person’s interests and activities. That is why the ritual book provides a wide choice of texts for the liturgy, to enable the rite to be adapted to the circumstances of the person’s life and death. But the purpose of the liturgy is not to celebrate the life of the deceased.

Liturgy is prayer; it is directed to God. It celebrates God’s grace and providence under which we live, the blessings we have received. It celebrates God’s mercy and compassion which does not hold our faults against us. It celebrates the death and resurrection of Jesus by which the hope of eternal life is given us. Sometimes in sorrow we lament; in anger or anguish we cry out for help. But a Catholic funeral is addressed to God in prayer.

Liturgy also ritualises a transformation in this life. The funeral helps us to redefine our relationship with the person who has died. After a period of sharing life and perhaps illness and old age, we bid the person farewell. Before we go our separate ways, says the presider, let us take leave of our brother/sister. May our last farewell express our affection for him/her, may it ease our sadness and strengthen our hope… The coffin is incensed as a sign of respect and we sing a song of farewell for the deceased. With God’s help, we are enabled to reconfigure our lives without the person who has died.

As we farewell the deceased from this world, we commend the person who has died to God’s care. It is a handing over. Often enough, a person who is terminally ill or advanced in years has already come to a point where they are ready to leave this world. They are ready to lay down their life before God. The Church gathered for a funeral supports this act in prayer or undertakes it on their behalf. As we let go, we entrust the person we know and love to the mercy of God, asking for a welcome into God’s arms of love. With Christ on the cross we say, Into your hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit. This is a release into a profound mystery, for we have very little idea of what happens after death. It is an act of trust in God. The person’s body returns to the dust from which it was made as the person returns to the hand of the Creator.

Our prayers for the deceased have a much more positive tone than they did in the funeral liturgy of the 1950s. Then it was filled with dread and the doom of judgement, with incessant pleas for the forgiveness of sins and deliverance from the gates of hell. One would think that our hope-filled liturgy today might be an encouragement to celebrate it well… except that so many people no longer believe. If they do not believe in an afterlife or the power of God’s grace, if they do not really believe in God at all, then what else is left for them to do but recount the deeds, the events and the small achievements of a person’s life?

In offering family and friends the opportunity to grieve and say goodbye to the person they have known and loved, the funeral rite provides consolation to the bereaved. But the greatest consolation comes from being able to insert this individual life into the great sweep of human history as God’s pilgrim people journey towards their homeland, the new Creation to which all God’s creatures are called.

For St Paul, it is our faith which brings us comfort:

We want you to be quite certain about those who have died, to make sure that you do not grieve about them, like the other people who have no hope. We believe that Jesus died and rose again, and that it will be the same for those who have died in Jesus: God will bring them with him… With such thoughts as these you should comfort one another. (1 Thess 4:13-14, 18)

TOM ELICH

Editor