Liturgy News

Vol 48 No 1 March 2018

Contents

| Title | Author | Topic | Page |

|---|---|---|---|

| Editor: Saviour of the World | Elich, Tom | Documents on Liturgy | 2-3 |

| New Directions Emerging in Liturgy | Hodgens, Eric | History of Liturgy / Vatican II | 3-6 |

| Understanding Posture in the Liturgy | - | Symbols | 6 |

| The Sound of a Church | Elich, Tom | Architecture and Environment | 7 |

| Our Lady of the Southern Cross - Springfield Lakes, Queensland | Elich, Tom | Architecture and Environment | 8-9 |

| Saint Paul VI | - | People | 10 |

| God = Hen | - | Liturgy - Other Churches/Religions | 10 |

| Blessing Same-Sex Couples | - | Special Celebrations | 10 |

| Communion in Mixed Marriages | - | Eucharist / Mass | 10 |

| Lay-led Funerals | - | Funerals | 10 |

| Why Sunday Mass? | - | Sunday | 10 |

| Frederic Debuyst | - | In Memoriam | 11 |

| Avoiding Temptation | - | Texts – Liturgical | 11 |

| Diabolical Attack | - | Eucharist / Mass | 11 |

| Mile-High Marriage | - | Marriage | 12 |

| Healthy Mass | - | Eucharist / Mass | 12 |

| Heavenly Bodies - Fashion and the Catholic Imagination | - | Art | 12 |

| Mary - Mother of the Church | - | Calendar | 12 |

| Familiarity Breeds | O'Brien, Jenny | Music | 13 |

| Acknowledgement of Country and Welcome to Country - Celebrating the Liturgy in Australia | Robinson, James | Indigenous Australians | 14-15 |

| Evangelising Young People into Liturgical Ministry | Hood, David | Evangelisation and Mission | 16 |

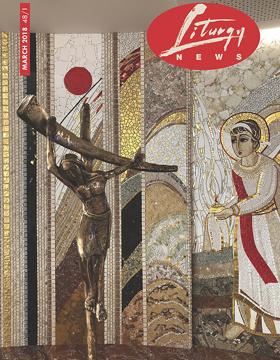

Editorial

SAVIOUR OF THE WORLD

Elich, Tom

The Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith has long had the reputation for acting as a draconian police force. I never thought I’d say it, but I am very pleased with its recent letter Placuit Deo. Although it tackles new forms of two ancient heresies, Pelagianism and Gnosticism, the tone of the letter is pastoral and its insights are perceptive, timely and balanced. There is a paragraph on the sacraments, but the implications of this letter for liturgy are more far reaching.

What issues is the document confronting? The new form of Pelagianism is seen in a growing individualism which recognises human fulfilment based only on a person’s own strength and efforts, and on human structures. Christ appears as a model who inspires generous actions by his words and example, but is not recognised as the one who actually transforms the human condition by incorporating us into a new existence, reconciling us with the Father by the gift of the Holy Spirit. It is the presumption that basically we can do it ourselves and so win God’s favour.

The new form of Gnosticism is seen in those who take a merely interior view of salvation, a vision marked by a strong personal conviction or feeling of being united with God, but which ignores the need to ‘accept, heal and renew our relationships with others and with the created world’. Here salvation is reduced to a subjective reality which presumes to liberate a person from the body and the material universe. It does not take into account the reality of the incarnation by which the Word became flesh, became a member of the human family and human history – for us and for our salvation. The provident hand of the Creator is no longer recognised in the material universe; it is simply a resource to be developed for human use.

Understanding and celebrating the liturgy well helps us to avoid both these deficiencies. Let us begin with the Pelagian tendency.

First and foremost, the liturgy is not a closed human activity but an opening where God acts in our midst. We encounter the Sacred, standing together in the presence of a God who is acting to save us. We read the words of Scripture, but it is God who calls to us. In baptism, we wash in water but it is God who plunges us into Jesus’ death and resurrection, and joins us to Christ and his Body the Church. In the Eucharist, we take bread and wine and make thanksgiving, but it is God who transforms our gifts, giving us the ultimate gift of Christ who is saving us by the sacrifice of the cross.

There is always this two-way movement in the liturgical action. God is actually doing something in the midst of the gathered Church, in our lives, in our world. Our actions are always a response to what God is already doing. We do not take the initiative. This faith is the ultimate counter to any Pelagian tendency.

Nevertheless, the temptation is strong. We come to Sunday Mass full of good will and go home feeling proud of ourselves that we have done something pleasing for God. In fact, God has done something very pleasing to us, and we have simply recognised and accepted this gift in gratitude and thanksgiving.

Lent is a particular challenge. It is not by accident that the first Sunday of Lent is always a reflection on Jesus’ temptation in the desert. Jesus is tempted to be self-sufficient but his clear affirmation in response to Satan is that he is utterly dependant on God in accomplishing his mission. That is our temptation too. During Lent, we fast and abstain, we give ourselves to prayer (Adoration, the Stations of the Cross, the Liturgy of the Hours), we undertake self-denial so that we might give alms to those in need. And we can easily imagine that we are doing something good ourselves, on our own initiative. To see all this aright, we need to understand that our conversion of heart and repentance of life is a humble response to God’s endless mercy and compassion.

This is also why the word merit is so dangerous in our liturgical texts. It has been unhelpfully reintroduced into our present translation of the Roman Missal. In Eucharistic Prayer II we hear: we may merit to be coheirs to eternal life. This is quite misleading because nothing we human beings do can ever merit or deserve eternal life. It is always God’s gratuitous gift. A grammatical analysis will show that the phrase is governed by the words Have mercy on us all.. Thus it is by God’s mercy that we merit. But we do not hear it like that because there are four lines in between to distract us. The usage in Eucharistic Prayer I is better: Admit us [into the company of the saints] not weighing our merits but granting us your pardon.

What about Gnostic tendencies? In the liturgy, God acts through bodily realities. Washing, anointing, eating, drinking, touching, hearing, speaking are essential elements of the sacramental moment when God acts. Sacraments are the windows we open to the sacred. They are a fundamental affirmation of the incarnation where God is present in the ‘flesh’ of the world and its history.

Finally the tendencies to both individualistic and spiritualised views of salvation are countered by a healthy understanding of liturgy as the work of the Church. The idea of liturgy as corporate worship – that is, the action of the Body of Christ – recognises the initiative of Christ in the liturgy and affirms our solidarity in worship with the action of the Church of all times and places. We cannot focus on our individual actions or interior vision when we are part of a community which encompasses the Churches in places of war, famine or exploitation. They become present to us as we stand at the altar in unity and as we are dismissed and sent into the world to go in peace to love and serve the Lord.

Placuit Deo places Christ, Saviour of the World, at the centre of the Christian faith. This joyful conviction is at the heart of the Church’s efforts at evangelisation. However this does not negate the loving embrace of God for all humanity and all of creation. This is why Christians ought establish sincere and constructive dialogue with believers of other religions in whose hearts God’s grace works in mysterious ways. Ultimately God calls all of humanity to salvation, to unity and fullness with God, our brothers and sisters, and all the rest of creation.

TOM ELICH

Editor