Liturgy News

Vol 50 No 2 Winter 2020

Contents

| Title | Author | Topic | Page |

|---|---|---|---|

| Editor: Discussing Eucharist | Elich, Tom | Eucharist / Mass | 2-5 |

| Corona Paraphernalia | - | Eucharist / Mass | 5 |

| Corona Pastoral Challenges | - | Eucharist / Mass | 5 |

| Sacramental Signs and Symbols - Love Story of our Lived Experience | Fort, Elizabeth | Sacraments | 6-7 |

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Sunday - Preparing Sunday Eucharist | Fitz-Herbert, John | Liturgical Inculturation | 8-9 |

| Liturgical Music - What's in a Name? | Crooks, Gerry | Music | 10-11 |

| In Memoriam: Geoffrey Wainwright | - | People | 11 |

| In Memoriam: Two Composers - Ray Repp and Shirley Murray | - | Music | 11 |

| Opening Up the Lockdown | - | Eucharist / Mass | 12 |

| Streaming Licence | - | Music | 12 |

| The Vatican Easter Directives | - | Easter and Lent | 12 |

| Extraordinary Form | - | History of Liturgy / Vatican II | 12 |

| Music Appointment - Christopher Trikilis | - | Music | 12 |

| Paul Turner at Liturgy Meeting | - | People | 12 |

| Seal of Confession | - | Penance | 13 |

| New Liturgical Books | - | Texts – Liturgical | 13 |

| Quote - Church after Pandemic | - | Evangelisation and Mission | 13 |

| First Parish Priest | - | People | 13 |

| Florence Nightingale | - | People | 13 |

| Books: The Parish IS the Curriculum. RCIA in the Midst of the Community by Diana Macalintal | Cronin, James | Christian Initiation | 14-15 |

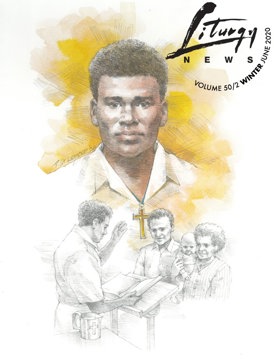

| Our Cover: Peter to Rot | Elich, Tom | People | 16 |

Editorial

Discussing Eucharist

Elich, Tom

The lockdown came very suddenly. On the second Sunday of Lent, we had new safety measures (no communion from the cup, no holy water, no sign of peace, hand sanitiser …). A fortnight later, churches were closed and we had no public Masses at all. Parish communities scrambled to find ways of staying connected and offering people support. For ten weeks, there was no liturgy or sacraments, not even for the great days of the Easter Triduum. At last, on Pentecost Sunday, we were allowed to open the church for Mass with tiny groups of ten people. After months of eucharistic fasting, many were eager to return to the church and celebrate Eucharist together.

During this time, most parishes made resources available – by email where possible or otherwise in hard copy. The best of these were focussed, consistent and restrained. They were accompanied by personal pastoral messages, encouraging families to read the scriptures together and reflect and pray. One of the benefits which many have experienced flowing from the lockdown, learning-at-home and work-from-home is a rich new family life – supported, we hope, by family prayer over the holy days of Easter and then week by week every Sunday since.

One of the most extraordinary manifestations of pastoral care has been the flourishing of live-streamed Masses from parish churches. A few of the larger churches and cathedrals already had the infrastructure in place to do this regularly for the sake of those who are aged or ill and consequently home-bound. Now, thanks to the wonders of technology, very many parishes have been able to live-stream the parish priest celebrating Mass in their empty church. This has been appreciated and valued by many people as a connection to their church and pastor in these exceptional circumstances.

Mass on screen however has been controversial. It has raised big theological and liturgical questions: what is real; what does it mean to be present; what is participation; what is the role of the priest; what place does receiving communion have in the Mass; and so on. I believe that one of the most important long-term theological benefits to come out of the pandemic might be that people around the world have been discussing Eucharist.

AN ABBERATION IS NOT THE NORM

It is disingenuous to pretend that there is no difference between a real-life Mass and a Mass on screen. Yet even an enlightened journal such as The Tablet published news from Shrewsbury Cathedral boasting that its Easter congregation was ten times the usual size due to Mass online, or the bishop in Wales who was delighted that Mass attendance had trebled thanks to online services. Others might reply that online hits are notoriously unreliable because the average time that people stay on the site might be 7 minutes or that people switch it on and then set about preparing the evening meal with the Mass playing in the background. Advocates cite examples such as World Youth Day, saying that Mass on screen would be preferable to a situation with a million people where some might be in a paddock a kilometre away using pre-consecrated hosts awaiting distribution from a tent.

Aberrant examples such as these are not helpful in trying to work out what is good, better or best practice in celebrating Eucharist. So to appreciate what Mass on screen might possibly offer, we need to imagine an ‘ideal’ family which is focussed on the liturgy. They light a candle, set up a cross, and stand sit and kneel at the appropriate times; they make the responses aloud; they download and print a worship leaflet so that they can sing the songs; they use a giving app to contribute to the parish at the preparation of the gifts. The priest and the readers address the people at home directly through the camera. In the best examples, there might even be possibilities for interaction, perhaps contributing intentions for the Prayer of the Faithful, and greeting other participants at the sign of peace. Is there pastoral contact established? Yes. Is there an opportunity for spiritual nourishment? Yes. Is there liturgical participation? Well, only to some extent.

What we have discovered in these months may enable us to reach out more effectively to the aged and infirm; it may help us deal with isolated areas where a priest is not available. But have we discovered a convenient and ‘modern’ alternative to a physical gathering in the church? I think not. How then do we understand and evaluate the possibilities and limitations of technology in celebrating the liturgy? We need to revisit a few basic liturgical principles.

TWO FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES

1. The Church/Christ is the celebrant of the liturgy.

The primary liturgical symbol is the assembly because the Church, the Body of Christ, is the celebrant of the liturgy. The ‘full, conscious and active participation’ of the gathered believers lies at the heart of the liturgy. Such involvement is the right and duty of all who are baptised into Christ (SC 14). ‘Active’ means that the baptised are present as doers of the liturgy, not just spectators, not just participating in what the priest is doing, but doing it themselves. The priest represents the headship of Christ in the assembly, presiding over the communal offering, but it is not his celebration.

This is the first and greatest challenge to Mass on screen. Responses and singing, gestures and posture only point to people’s real participation which is the actual communal ‘doing’ of Eucharist by the whole Body of Christ. Live-streamed Mass gives the opposite message. It lets people imagine that the liturgical action belongs to the priest alone. He celebrates in a virtually empty church accompanied by his camera operator. He is encouraged to celebrate ‘his’ Mass on Sundays while the people, forced to sit at home and fast from communion, are sidelined and can only watch.

As part of the recent debate on Eucharist, Felix Just SJ (Real Presence and Virtual Liturgies) has correctly pointed out that the difference between Mass on screen and Mass in church is not that one is ‘virtual’ and the other is ‘real’; rather the distinction is between two kinds of ‘real’ – one virtual and the other physical. The problem with Mass on screen for me is that, in virtual reality, you cannot actually do something; it is presented to you. We have discovered more than ever that the electronic media (email, Skype, Zoom, etc) are great for communication. We can disseminate information, have meetings, exchange ideas and make decisions; we can make real connections with people who are distant; but we cannot physically do something together which is what the liturgy requires. Like food programs on TV which teach us to cook, we don’t smell or taste anything.

This experience of virtual reality feeds into the withdrawal we have witnessed over recent decades from the Vatican II terminology of presbyter (elder/presider), back into notions of the cultic priesthood – a priest who offers sacrifice and acts as mediator between heaven and earth. The persistence of the idea of the parish priest offering a weekly Mass pro populo is a sign of this understanding which has opened such an easy path to the live-streaming of Mass. So too have the ubiquitous illustrations in children’s Mass books and catechetical resources which show only what the priest is doing at the altar. Notwithstanding the deep pastoral instinct and desire behind Mass on screen, the practice has slipped into an alarming form of clericalism and has marginalised the assembly of the baptised, excluding them from any essential role in the celebration of the Eucharist.

2. Real presence is Sacramental presence.

Imagine that I have been to visit my grandma who is dying and whom I may never see again. I am going home on the train and am seated beside a person whose weight leans against my side. But my mind and heart are totally occupied with grandma and our leave-taking. When I arrive at my destination, I really couldn’t tell you who was sitting beside me. Who is really present to me in that train journey? Not all presence requires physical proximity. Technology can make distant people really present to one another and can enable them to connect.

Why then is someone’s presence by electronic means unsuitable for celebrating the liturgy? What is unique about the liturgy is that it deals with sacraments. The whole idea of sacrament is that it has an anchor in physical reality. Felix Just rightly notes that sacramental reality is not to be confused with physical reality – Christ is not ‘physically’ present in the Eucharist as he was present to his disciples 2000 years ago. But that does not by any means reduce a sacramental presence to something symbolic which can be accessed virtually. The real sacramental presence of Christ requires actual bread, broken and eaten, actual wine, poured out and drunk. This sacrament is the means by which we are united to God.

That is why we are no longer satisfied with the minimal requirements for making a valid sacrament. Sacramental theology for the last half century has emphasised the power of the sacramental sign to lead us into the divine mystery. So we are encouraged to baptise by immersion or at least pour water abundantly; we smear oil liberally on the forehead, not just dab it from a moist ball of cotton wool; we are encouraged to use real bread that can be broken and shared at the altar and receive communion from the common cup. These sacramental signs are windows which open the vista of God’s love. By making them well, we have clean windows which do not obscure the view beyond.

Vatican II encourages us to recognise that Christ is present at Mass not only in the consecrated bread and cup, but also in the assembly of the Church, in the word proclaimed and in the ordained minister. Now these too are part of a sacramental reality – a real assembly of the faithful, not photos taped to the pews; the word proclaimed viva voce from mouth to ear, not something which emerges electronically from a speaker; the pastoral human presence of the priest among the people of God. Obviously in lockdown, it is precisely these sacramental signs which have been impossible. Pictures on screen of the liturgy and its sacramental signs might be the best we can do and might remind people of a reality we cannot access for the present. But it cannot be a permanent way forward for Christian people in an electronic age, no matter how much our identity, attitudes and relationships are shaped by social media.

Mass on screen entangles us in a double bind. Sacramental signs are received in faith; they mean something in a community of faith. What is it doing to take these, our most sacred rites, and open them to the public gaze of the hoi polloi? I have the same reaction when a Corpus Christi procession with the monstrance goes through the shopping mall of a secular city. Evangelisation invites people into the sacred mystery; it does not instrumentalise it. On the other hand, Mass on screen privatises what is meant to be a corporate act when each person in their lounge room is encouraged to make a ‘spiritual communion’. This devotional prayer might be spiritually helpful, but it has little to do with actual sacramental communion. To maintain that it was common Catholic practice until the 20th century to attend Mass and not receive the sacrament is hardly an argument; it merely confirms that Mass on screen normalises a regression to an outmoded theology and practice. Far better, in my view, to fast from the Eucharist together and stir up a deep yearning for what we have lost, than to persuade ourselves that we can do something just as good in our hearts.

Pope Francis, who has been celebrating live-streamed Mass, remarked that this is the Church of a difficult situation… the ideal of the Church is always with the people and with the sacraments – always! … Be careful not to virtualise the Church, to virtualise the sacraments, to virtualise the People of God. The Church, the sacraments, the People of God are concrete.

A WAY FORWARD FOR MEDIA AND LITURGY

Live-streamed Masses provide important connections in extraordinary circumstances, not only in pandemic lockdown, but also for those who are not able to be present (the sick and infirm, family overseas) or where isolated communities do not have access to the church community. But they do not offer a regular alternative means for liturgical participation.

Live-streamed Mass is always preferable to Mass that is recorded and broadcast later or made available ‘on demand’. This is because it is a real-time connection to an actual liturgical event. I have long had serious issues with Mass for You at Home, Australia’s longest running religious television program (established in 1971). To make this program, three Masses are celebrated back to back in a television studio, months before the broadcast date. How is this the proper context for celebrating Eucharist: in a studio with camera operators and a ‘show congregation’, doing Christmas-Epiphany Masses one after another in August? The German bishops as long ago as 1989 and the USA bishops in 1996 were both very negative about these kinds of arrangements, insisting on a single Mass with a living congregation celebrated on the correct liturgical day in a church. Perhaps our experience with new technology and live streaming can put this program to rest once and for all in favour of something better.

While our pandemic experience has brought many of us to realise that electronic media are fundamentally unsuitable for liturgy, we have also learned how helpful it can be for broader spiritual and educational activities. Online retreats, prayer reflections and readings support the Christian life, and may prepare for liturgical celebration and may unfold its meaning afterwards.

The great theologian Karl Rahner died in 1984 before the internet or social media; he made this comment in the early years of television in the late 1950s. How do we respond to this challenging remark sixty years after he wrote? He said that the desire to be modern may soon turn out to be highly un-modern. Once the TV set has become part of the ordinary furniture of the average person, and once someone is used to being the spectator of just about anything between heaven and earth upon which an indiscriminately curious camera preys, then it will be an unbelievably exciting thing for the philistine of the twenty-first century that there are still things which one cannot [just] view while sitting in a recliner and chewing on a burger.