Liturgy News

Vol 46 No 4 December 2016

Contents

| Title | Author | Topic | Page |

|---|---|---|---|

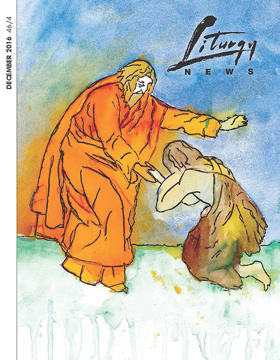

| Our Cover - The Prodigal Son and the Merciful Father | - | Mercy | 1, 16 |

| Editor: Wrong-footed Rules | Elich, Tom | Documents on Liturgy | 2-3 |

| Triumph of Love in Death | - | Liturgy - Other Churches/Religions | 3 |

| Ukrainian Eastern Worship - Key Learnings for the West | Kelty, Brian J | Liturgy - Other Churches/Religions | 4-5 |

| Turning Seekers Into Disciples | Schwantes, Clare | Christian Initiation | 6-7 |

| Congratulations - Jerry Austin | - | People | 8 |

| Mercy and Misery | - | Mercy | 8 |

| Reject Rigidity | - | Eucharist / Mass | 8 |

| Ratio for Seminaries | - | Documents on Liturgy | 8 |

| Heavenly Vaults | - | Architecture and Environment | 9 |

| ACU Centre for Liturgy | - | Catechesis - liturgical | 9 |

| Playing Favourites | - | Texts – Liturgical | 10 |

| Reconciliation Chapels | - | Penance | 10 |

| New Missal in Korean | - | Texts – Liturgical | 10 |

| The Summit | - | Texts – Liturgical | 10 |

| Commemorating Martin Luther | - | Liturgy - Other Churches/Religions | 10 |

| Membership of Worship Congregation | - | People | 11 |

| Diaconate and Women | - | Ministries – Liturgical | 11 |

| Adelaide's New Organ | - | Music | 11 |

| Singing the National Anthem at Mass on Australia Day | - | Music | 12 |

| WWW - Weally Worthwhile Websites - National Liturgy Offices | Harrington, Elizabeth | Technology | 12 |

| Confession and the Royal Commission | Elich, Tom | Penance | 13 |

| Preparing for a Funeral Liturgy - The Role of Children's Literature | Schwantes, Clare | Funerals | 14-15 |

Editorial

WRONG-FOOTED RULES

Elich, Tom

The people of our time stand uneasily before the mystery of death. They want to remember and venerate the person they love who has died. They can tell stories and eulogise. But what else can they do?

Christian funeral rites can support the bereaved; the faith enshrined in the liturgy can articulate for them the mysterious shape of life after death. As the dead person leaves our arms – arms that may have nursed them in age or illness – we commend him or her into the arms of God’s love and mercy. God, who cares for us in life, receives us and holds us in death.

The resurrection of Jesus is one of the fundamental planks of Christian belief. Because of this, we know that Christ is alive and present in the Church, in word and sacrament. Our baptism makes it personal. Each person is thus joined to the Body of Christ and follows Christ in life and in death. Because of Christ, Christian death has a positive meaning. As the liturgy says, Indeed for your faithful, Lord, life is changed not ended, and, when this earthly dwelling turns to dust, an eternal dwelling is made ready for them in heaven.

The Rite of Committal of a person’s earthly remains affirms that the place which claims our mortal bodies becomes a sign of hope that also promises resurrection. The way we treat a body in death affirms the dignity of the human person, and that is why care of the dead is listed among the corporal works of mercy.

Christian faith in the doctrine of the communion of saints further affirms a profound solidarity between the living and dead. The spiritual union between Christian people and those who have passed through the veil of death offers the bereaved comfort for themselves and an opportunity to assist the deceased through prayer. We intercede for one another in this life and beyond this life. The liturgy encourages this in the twin feasts of All Saints and All Souls.

Reflections such as this are theologically sound and pastorally helpful in accompanying the bereaved and in strengthening the faithful as they confront death.

All these things are outlined in an Instruction To Rise with Christ issued by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith on 15 August 2016. Notwithstanding this inspiring teaching, the Congregation has managed to produce a statement which will offend many for, half way through this short document, its tone changes. The bee in their bonnet is the issue of burial versus cremation and the ‘correct’ way to treat the ashes after cremation.

We cannot condone erroneous ideas about death, the Instruction states, considering death as the definitive annihilation of the person, or the moment of fusion with Mother Nature or the universe, or as a stage in the cycle of regeneration, or as the definitive liberation from the ‘prison’ of the body. This is the prelude to the treatment of cremation. Of course the Instruction acknowledges that the Church has no doctrinal objections to cremation, but claims that burial shows a greater esteem towards the deceased. It envisages cremation may be chosen for sanitary, economic or social considerations. Cold language! It wounds Catholics who have chosen cremation for themselves or their loved one.

The Congregation states that ashes must be laid to rest in a sacred place. This is defined as a cemetery or an area set aside for this purpose and dedicated by Church authority. This will ensure that the dead are not excluded from the prayers of the Christian community and will prevent them from being forgotten after a generation. On the one hand, we have here a beautiful rationale for parishes to establish a columbarium in or near their church. This laudable practice is increasing and is an excellent way to express the communion of saints and our interdependence in prayer. It captures the spirit of the churchyard of old. On the other hand, it does not represent the reality of many of our large urban cemeteries and the endless walls of niches at our public crematoriums. These are frequently vast, soulless and anonymous places which hardly recognise the dignity of the children of God.

The Instruction then forbids the conservation of ashes in a domestic situation and the practice of dividing them among family members. Next, it forbids the scattering of a person’s ashes in the air, on land or at sea, citing the appearance of pantheism, naturalism or nihilism. The presumption of bad faith in these practices is offensive to those who have carried them out with the greatest love and respect for the deceased.

The Congregation would have done well to concentrate on the principles of Christian hope and honouring the dead, without descending to the practicalities of burial and cremation. These are shaped by local tradition and culturally determined. Alternative practice need not compromise in any way the principles which Christian burial is said to safeguard.

In addition the Instruction shows an alarming lack of historical perspective. In the Middle Ages most ordinary folk were interred in mass graves. The bodies of royalty were frequently dismembered so that their head, heart and body could be interred in different places. The bodies of the saints were likewise split apart, for to multiply the locations of the saint’s remains was to multiply the devotion.

Andrew Hamilton SJ, always a wise and balanced commentator, writes in Eureka Street (1 November 2016): Certainly, cremation is open to possibilities that the Instruction does not envisage. Sprinkling the ashes over the sea or a place significant to the dead person, for example, can be consistent with an informed Christian sensibility. It need not be pantheistic. In the lives of many Catholics, Paradise places are deeply significant. These are places where they have experienced a deep sense of God’s presence or calling and which, when remembered, lead them easily into prayer. In wishing to have their ashes sprinkled there they may express thanksgiving for the gift of God’s creation and also their hope for the transformation, not only of their own bodily existence, but also that of the natural world in the final resurrection. While loaded with personal significance, this gesture need not simply express an individual whim, still less withdraw the dead person from their community and its memory. The significance of the person and of the place where the ashes are scattered will be held in the stories and memories of those present at their funerals. And the place associated with them may trigger memory in the same way as would a graveyard.

This final remark presumes that the dispersal of the ashes is an integral part of the Order of Christian Funerals. Sometimes, when there is to be a cremation, the funeral liturgy in the church is followed by a Rite of Committal at the hearse or at the crematorium. When the ashes are ready, they are given to the family and, unless there is a parish columbarium, the Church has no further involvement. This is a mistake.

We ought to forget about the intermediate step of the crematorium and celebrate the Rite of Committal at a time prearranged with the family for the disposition of the ashes – at a gravesite, in a columbarium or wherever. This rite, adapted to the circumstances, will honour the faith of the bereaved, offer respect for the deceased person and help to create a sacred place of memorial by the very act of placing or dispersing the ashes in the context of the liturgy.

TOM ELICH

Editor