Liturgy News

Vol 50 No 3 Spring 2020

Contents

| Title | Author | Topic | Page |

|---|---|---|---|

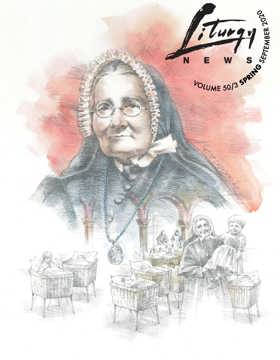

| Our Cover: Venerable Suzanne Aubert | - | People | 1, 16 |

| Editor: Liturgy and Governance | Elich, Tom | Liturgy and Governance | 2 |

| Talking Together - Working Together | Schwantes, Clare | Liturgy and Governance | 3-5 |

| Listen to What the Spirit is Saying - Liturgy in the Plenary Documents | Willison, Kerry | Documents on Liturgy | 6-8 |

| Belonging to a Land | McGoldrick, Clint | Indigenous Australians | 9 |

| Order of Christian Funerals | O’Rourke, Ursula | Funerals | 10-11 |

| Translation Change | - | Texts – Liturgical | 11 |

| Italian Missal | - | Texts – Liturgical | 11 |

| Human Solidarity | - | Documents on Liturgy | 11 |

| Christchurch Cathedral | - | Architecture and Environment | 11 |

| Baptism Formula | - | Baptism | 12 |

| The Light From the Southern Cross | - | Liturgy and Governance | 12 |

| New Font | - | Architecture and Environment | 12 |

| Covid Choirs | - | Music | 12 |

| Lectionary Translation | - | Texts – Liturgical | 13 |

| Parish Pastoral Conversion | - | Documents on Liturgy | 13 |

| Broken Bay Confirmation | - | Confirmation | 13 |

| Liturgy Educator | - | People | 13 |

| Cathedral Bells | - | Architecture and Environment | 13 |

| In Memoriam - Lindsay Farrell and Ernst Fries | - | In Memoriam | 14 |

| Return With Joy | - | Liturgy and Governance | 14 |

| Books: A Parish Guide for Bereavement Ministry and Funeral Planning by Jill Maria Murdy | Cronin, James | Funerals | 14-15 |

Editorial

Liturgy and Governance

Elich, Tom

Church governance has been in the news of late. The Australian Church has received the report on promoting co-responsible governance, Light from the Southern Cross. It originated in the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse but its scope is much broader. Governance concerns authority, leadership and accountability. This includes the relationships of responsibility and the centres of agency within the Church. The report connects with and will feed into a number of themes emerging in the preparatory documents for the Plenary Council due to be held in 2021-2022.

Over the last decade, Pope Francis has consistently articulated a collaborative, synodal and decentralised ecclesiology. This has tended to circumscribe the overweening micromanagement of the Roman Curia and is a powerful expression of a Vatican II theology. Lumen Gentium, the document on the Church, began with a chapter on the People of God before it tackled the Church’s hierarchical structure, an approach carried through in the 1994 Catechism of the Catholic Church. At the end of June, we received the curious schizophrenic document, The Pastoral Conversion of the Parish Community in the Service of the Evangelising Mission of the Church from the Congregation for the Clergy in Rome.

The first half acknowledges that increased mobility and the digital culture challenge traditional parish structures. It articulates a vision of dialogue, solidarity and openness to others based on a rediscovery of the vocation of all the baptised. The whole community, and not simply the hierarchy, is the responsible agent of mission, since the Church is identified as the entire People of God.

But there is a dramatic change of gear half way through the document. Suddenly it is all about the Bishop, the Presbyteral Council and the Parish Priest. Lay Pastoral or Financial Councils are only consultative. Lay leaders cannot be called ‘pastor’, ‘chaplain’, ‘moderator’, or ‘manager’. Notions of co-responsibility evaporate.

The thinking of Light from the Southern Cross is aligned with the first half of the document on the parish; it speaks of a complementary and collaborative ministry centred on the liturgy. It is in the parish that communities of the faithful come together, forming a eucharistic community: a community of prayer, of mutual service and apostolic works. The parish is a liturgical community, caring for one another and missionary in outlook. It is here that the local church is actualised as priest and people together form a community of the faithful united around the local bishop (4.5 and 7.2.5).

I suggest that the liturgy has a fundamental contribution to make to our deliberations on governance. The idea that the liturgical assembly is congruent with the organisation of the whole Church is embedded in the teaching of Vatican II. The preeminent manifestation of the Church is present in the full, active participation of all God’s holy people in these liturgical celebrations, especially in the same Eucharist, in a single prayer, at one altar at which the bishop presides, surrounded by his college of priests and by his ministers (SC 41).

This insight is generally interpreted to say that the Church’s hierarchical structure must be expressed in the articulation of different ministries in the liturgy. The design of the liturgical space ought show the differentiation of ministry and order; the parts of the Mass and the texts assigned to each must manifest right order; vesture, gesture and movement also identify each one’s place in a hierarchical structure. But I think this notion can be flipped on its head.

Liturgical participation, full and active, is everyone’s right and duty by virtue of their baptism (SC 14). Who celebrates the liturgy, asks the Catechism? Liturgy, it answers, is an action of the ‘whole Christ’ (CCC 1136); that is, it is the action of the whole community of the baptised which constitutes the Body of Christ. Ordination does not supersede or override one’s baptism; it enriches it with a special leadership of service of others. The priest facilitates the work of the community of the baptised.

This liturgical vision of the Church at prayer suggests that genuine co-responsibility in leading and directing the Church is an ideal worth striving for. When lay women and men have key leadership roles in the local Church, when they work collaboratively alongside the bishop or parish priest in decision making, they are exercising their role as a ‘chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s own people’ (1 Pet 2:9) and displaying the right relationships as established in the liturgy at the Table of the Eucharist.

In Christian usage, the word ‘church’ designates the liturgical assembly, but also the local community or the whole universal community of believers. These three meanings are inseparable. ‘The Church’ is the People that God gathers in the whole world. She exists in local communities and is made real as a liturgical, above all eucharistic, assembly. She draws her life from the word and the Body of Christ and so herself becomes Christ’s Body (CCC 752).

A problem arises when a clericalist view of Church organisation and governance goes hand in hand with a clericalist view of the liturgy. In a parish where the priest is considered the one who does the liturgical action and people are taken as mere passive spectators, it will not be surprising that he is also seen as the community decision maker and the people (whether they offer advice or not) are the ones who follow. It might be time for us to take our liturgical words more literally: Grant that we, who are nourished by the Body and Blood of your Son and filled with his Holy Spirit, may become one body, one spirit in Christ (EPIII).